“Well, ma’am, you know what Archimedes always said?” asked Justin via phone, a man I’d met 30 minutes prior through Facebook Marketplace in my efforts to sell a long-unused 6-foot heavy wood and metal martial arts training equipment filled with sand called a Wooden Man.

While working out the transaction details, Justin told me at length about his struggles with work, recovery, holding down a job, getting an ADHD diagnosis and meds to help – all part of why buying this equipment felt so important to him to help him get back on track in his life. The logistics of this sale were tricky – requiring me to perfectly time a pit stop 3 hours into a 6-hour road trip to pick up my kids from a spring break adventure they were on. And if Justin were to flake on me, as so many do on Facebook Marketplace, there would be no room in the car for my kids’ suitcases and beach gear on the drive back and the Wooden Man would have to be abandoned between a Cracker Barrel and an Exxon in Charlotte, NC.

“No ma’am, I’ve got the cash. I’ve set my alarm set and I set a second alarm my ex-girlfriend gave me. I will be there,” Justin reassured me. If he wasn’t the good person he turned out to be, he might have simply lied in wait behind that Cracker Barrel until he saw a harried, angry middle aged lady wrestle a large sand filled leviathan out of the back of her Telluride and heave it bitterly towards the dumpster.

But he wasn’t. Justin was a good egg, responding good naturedly when I called back to say I’d hit a snag – I didn’t have the upper body strength to hoist it into the back of my car.

“Well, ma’am, you know what Archimedes always said?”

I love it when my own latent snobbism is called to the mat, giving me another shot at scrubbing it. I didn’t expect this young man, who already had lived through such challenges by his early 20’s, to tell me about Archimedes.

“No, I don’t. What did he say?”

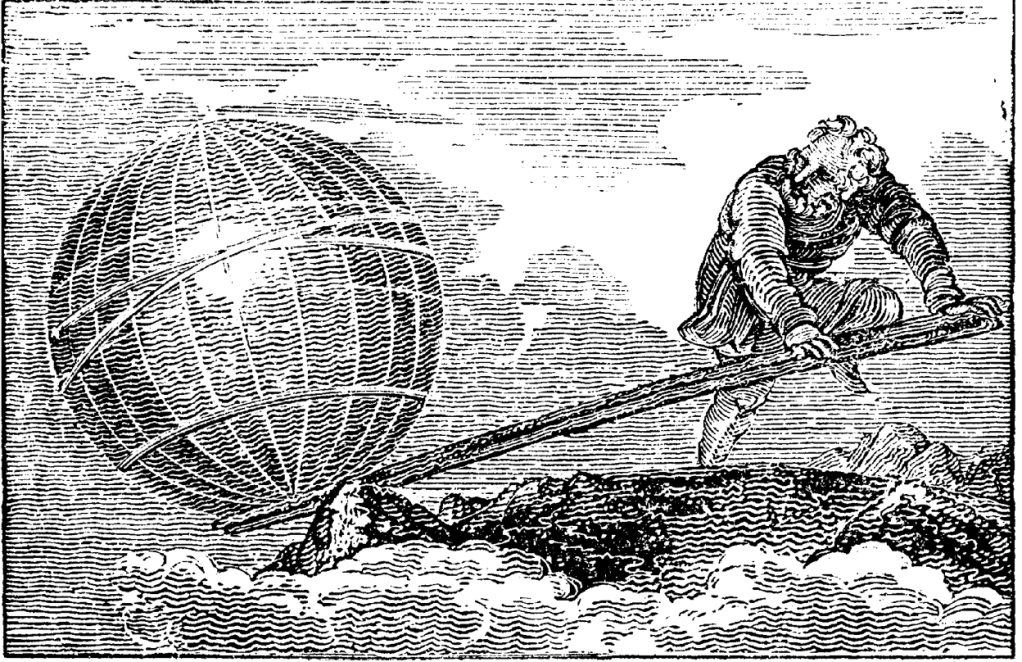

Justin went on pleasantly. “Archimedes said, ‘Give me a lever and fulcrum and I can move the world.’ And ma’am, you can almost always find something to use as a lever. Just look around your garage – plywood, cardboard.” He paused and drew a big dramatic breath, “You’d be AMAZED by what you can do with cardboard!!!”

I could tell there was a real excitement and energy there about cardboard – probably a couple of great stories about feats of impossible human strength pulled off by broken down Amazon boxes, but I felt the need to hurry off the phone with this new information and inspired advice and give it a go.

“It worked! Go, Archimedes!” I texted 10 minutes later and he shot me back a thumbs up and what appeared to be a Parthenon emoji with the reply, “Fuck yeah!!” I told a friend about it all laughingly at dinner that night and she told me it’s only a good story once I made it back safely and insisted I drop a pin of the meetup Exxon. But Justin made good on the rendezvous the next day and now, months later, it’s nice to imagine him whaling on that Wooden Dummy after work as a security guard in Raleigh, saving up for his own place and dreaming about big shit he can move with some extra heavy cardboard and an ingeniously-placed fulcrum.

While I was sliding that cardboard between the car and the Wooden Man back in March, I think there was a flattened refrigerator box being slid between me and my world.

Like a lever on a really stable and big fulcrum, it was a subtle lift and shift – one that I wouldn’t feel for months, not until the dizzying excitement that I’d left the ground and was gently being put down in a slightly new place. Transitions are like that. I had looked up Archimedes quote and thought it interesting – debates about translations aside – that a fuller version read: “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.”

I’ve become expert at cramming tiny spades and butter knives into nooks to try to move what’s heavy or stuck and needs adjusting in my world. It’s sometimes successful, sometimes not. But oh, the long lever! That’s where the real movement happens and requires so much positioning, aligning, and fully addressing the weight of the thing to be moved.

Just before the spring break road trip – Facebook marketplace adventure, a dear friend came to visit and I sat on the couch with her and described the subterranean reservoir of lonely I was feeling. It was as though I was standing at the shore of its dark, deep waters – all I had lived and lost and thought would be my future contained inside, and it was so vast and so dark I couldn’t see the banks of the other side, any other possible reality. How do you move a lake?

With a lever long enough.

I think the first positioning of that lever must have been in being willing to talk about the Big Sad of that feeling – with safe friends over the past couple of years. You have to take an honest and accurate measure of the heft and size of what you want moved. And then once it’s in place, and you’ve opened your heart to possibility, to movement, and leaned all your body weight into it, it’s patience. God, I resent and hate this so much. Will I ever learn to be patient? (Will I? When? When? When????). In the movement of big things with long levers, nothing happens for the longest and it all looks like stagnancy and failure and flies buzzing and sore shoulders for the effort.

Then a shift. The kind where you can tell, you’ve got the underbelly of the thing – not grazing a slippery side – but the very seat of it.

My lake isn’t moved, but it’s moving. I’m not naïve enough to think that it will never not be a reservoir — the edges of its banks rising and falling with my heart – but what’s changing is its placement and its tributaries in and out. It’s moving from the stagnancy of a crater lake to one fed by rivers and streams. The long lever has shifted the pain and loneliness to something that also contains possibility and hope.

Timing, patience, willingness to lean one’s shoulder into a herculean effort – these are necessary for lake-moving, but so is paying attention and meaning making. To move something, we have to imagine its shape-shifting possibility as well as our own possibility to be willing and hopeful and vulnerable enough to make a fervent little wish. This isn’t possible when we are in the tunnel vision of pain. In Something in the Woods Loves You Jarod Anderson writes about how meaning-making is a creative collaboration between us and our relationships with others or nature that has true generative power to leverage our lives. The act of seeing meaning in a great heron spreading its impossibly long wings over the water in flight is a creative collaboration between the heron showing up and our own imagination to connect this witnessing to our life’s burdens and hopes.

Anderson says if we don’t think a heron is magic, we need to broaden our definition of that word, as he breaks down the avenues to get there:

“There are two paths to magic: Imagination and paying attention. Imagination is the fiction we love, the truths built of falsehoods, glowing dust on the water’s surface. Paying attention is about intentional noticing, participating in making meaning to lend new weight to our world. An acorn. The geometry of a beehive. The complexity of whale song. The perfect slowness of a heron.

Real magic requires your intention, your choice to harmonize. Of course it does. The heron cannot cast starlight onto the dark shallows to entrance the bluegills. Not unless you do your part. You must choose to meet her halfway. And when you do, you may find that magic isn’t a dismissal of what is real. It’s a synthesis of it, the nectar of fact becoming the honey of meaning.”

I think for me, and maybe this is true for you too, that honey of meaning is required fuel to keep going when something is being moved by a long lever. It’s sustaining and gives hope and tiny encouragements. It’s why I write. It’s why I walk the trails behind my house up to the highest spot and look at the mountains. Those old blue brontosaurus-backed mountains are showing up for me, and I’m seeing in them the meaning I need to keep going, keep imagining, while the long lever does its slow lake-moving work.

“Go Archimedes!”

“Fuck yeah!”