It’s funny how the advice of a sex columnist can help you get to a happier place with your youngest child’s day care. I’m sure we’ve all had this experience, right?

See, I have this thing about food, particularly food that my offspring puts in their respective tiny mouths. Categorize under my long list of “tiny, hardly-worth-mentioning control issues”, but I’ll stand by this one as a battle I’m willing to undertake … at least in the early years… at least most of the time.

I had temporarily forgotten a) that I cared so much about my children’s food and 2) that I had agency to address it until recently, when I remembered Dan Savage’s often incendiary, always hilarious and spot-on column, “Savage Love.”

Let me explain. When my twins were wee — back when I had vim and vigor and no grays and would do things like carefully freeze the baby food I’d made them in ice cube trays – they grew up eating all kinds of “growing foods.” Sure, it took a little special marketing: green beans were magic wands, broccoli were baby trees, kale chips were, and still are, Shrek chips – but it worked.

It largely worked because I kept them home over half the time until they were 4, and we were surrounded by a supportive organic/healthy food environment in Northern Virginia, so they didn’t see an Oreo until kindergarten. Don’t get me wrong – they now have the shaky pupils and micro-attention span of any other red-blooded 3rd grader badly in need of either a starburst fix or a 28-day lock down sugar-rehab. But they are sane and healthy and so far, no one has premature boobs or type 2 diabetes, and for a little while there, for just a little while – it was the land of (no growth hormone) milk and (raw, local) honey. I’ll never forget us having a playdate circa 2010 and Henry running from where I was in the kitchen to where his friends were in the playroom and excitedly shouting, just like that kid on the Stouffer’s Stovetop Stuffing commercial, “You Guys – My mom’s making ASPARAGUS!!”

Crickets.

I think I remember one kid putting down a Lego reeeeeallly slow.

When the baby came along 6 years later, and I was all out of vim, much less vigor and ice cube trays, and we were all eyeball deep in Oreos (albeit the Newman’s Own brand), I decided that store bought organic baby food, free of corn syrup and dyes and weird ingredients, would be enough. In the land of good enough parenting, this was still a win.

When August began at our wonderfully diverse daycare and preschool, which serves children with developmental disabilities as well as those that qualify for early head start – I loved everything about it except the food.

I spent a year complaining to everyone who stood within earshot of my kitchen island about the fact my 6-month-old with four teeth was fed a Poptart. I got into that weird, crazy controlling place – passive aggressively trying to fill him up on yogurt and homemade applesauce at home, so maybe he’d be too full to eat a breakfast of Lucky Charms at school. I even asked my pediatrician to write that he wasn’t allowed to have high fructose corn syrup because he had a condition called “healthy baby.” But the only thing this succeeded in doing was making me have short, sharp teeth. I then remembered a particular Dan Savage column, and its salient message: You have a problem? Open your mouth and solve it. Say what it is you want, offer a solution, make it better. Period.

I went into the day care director’s office the next day and asked if I could help her by forming a parent’s committee to revamp the school menus. “Oh, would you??” was her instant reply. With no resistance, with total support, a few other parents and I renegotiated with the vendor, changed the menus and inventory, brought in organic milk from a local dairy, and found funds to build a schoolyard garden. Help rose up all around me like so much Louisiana kudzu, other parents bringing shovels and wheelbarrows, some offering herbs and pots, the administration and teachers leading the way. I’ve no doubt there was some serious luck and magic and good timing at work. AND – speaking up and being willing to work activated all that good juju.

Even though I knew I got lucky, it was hard to believe my unhappiness with the daycare’s food could be so simply remedied by my addressing the problem and being willing to help fix it. What was more surprising: that it worked — or that I had become so used to thinking about myself as impotent in the face of my frustrations to be surprised that it worked?

I think one of the reasons that Open Your Mouth, Solve Your Problems can be such a hard task for so many of us is because we feel so damned overwhelmed so much of the time. I’m overwhelmed in the produce section of the grocery (what were the 12 fruits and vegetables with the heaviest pesticides?), in my kitchen (wrapping up a work email, trying to throw together a dinner lickety-split so that 80% of my family can hurry up and reject it), at the macro-level (that my town has one of the worst health profiles nationally is as much a function of deeply, generationally institutionalized race problems as it is of poverty) …. And y’all, that’s just on the subject of food.

This is one of the reasons the price of pinot noir has skyrocketed and Barnes and Noble now has an entire section dedicated to adult coloring books.

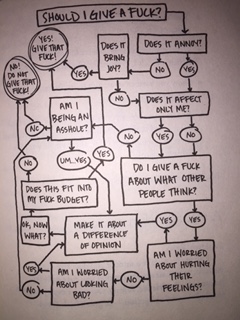

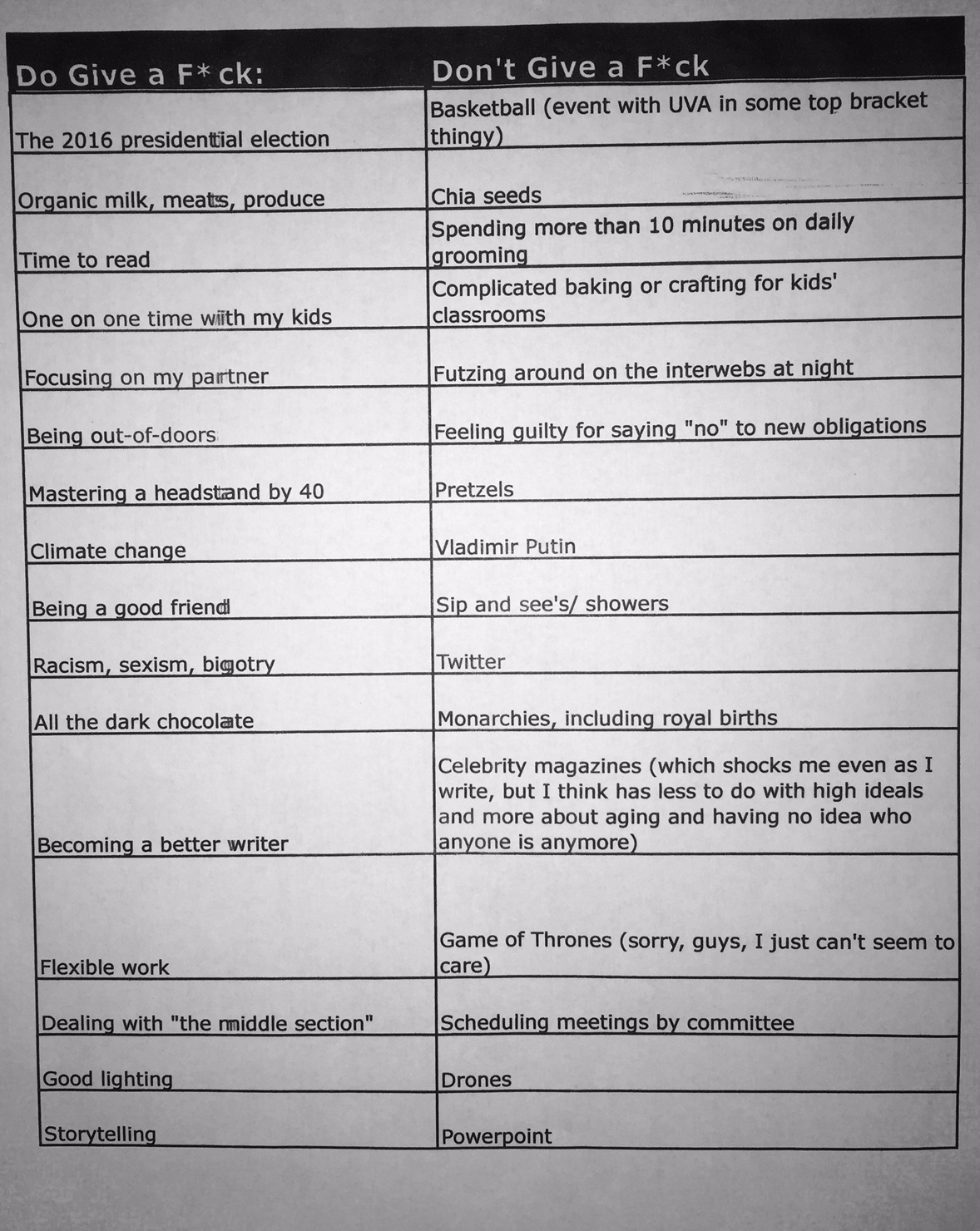

But Dan Savage says just start, just open your mouth, and start by being honest and clear with yourself. Nevermind he’s often talking to a 23-year-old bi trying to sort out sex-positive experimentation or redefining “saddlebacking”, the message still resonates. We kvetch plenty, but do we try to take the issue to the table and say, “hey – here’s the thing: This isn’t working. Let’s fix it, together. I see the following two options…” ?

Not for me. I find it far easier to silently seethe and bitterly resent you for not reading my mind.

This can be big, scary, heroic stuff. To move toward the thing you want (and are acutely, and sometimes, painfully aware is missing). When I’ve lost something important, I don’t want to look for it – I’m so afraid I’ll confirm my fears its gone. I move away, try to ignore it, but like a bad tooth, my tongue seeks it out over and over. When I feel like something in my life is not working, I talk endlessly about it, for years, to anyone foolish enough to ring me up or sit across a table from me. Or I purposely talk not at all about it, but think and obsess about it constantly. I might address it, sure, but only in fits and starts. I can’t escape these things, but I can understand first hand so well how we all try to. Until there is an Open Your Mouth breakthrough.

I have a dear friend, whose decided she’s going to have that baby she’s been yearning for, with or without a partner. She’s going to huge lengths, flying in from far away by herself for fertility treatments, having the incredible audacity and bravery to hope (which of course means she will become a mother, one way or another). She’s opened her mouth, she’s walking out the hard road of solving her problems, she’s turned towards it instead of away from it. She’s my hero.

Life is a momentum game. But we have to try in this very soldierly left-foot right-foot left-foot way. We have to walk towards the pain or the loss. Towards even our own miserable kvetchiness. “What does it mean to lean in to grief?,” a friend once mused aloud to me. We only know it by its counterfactual, by what it’s not. We know it means not moving away from it. It means not Fearing Paris.

Fearing Paris

by Marsha Truman Cooper

Suppose that what you fear

could be trapped

and held in Paris.

Then you would have

the courage to go

everywhere in the world.

All the directions of the compass

open to you,

except the degrees east or west

of true north

that lead to Paris.

Still, you wouldn’t dare

put your toes

smack dab on the city limit line.

You’re not really willing

to stand on a mountainside,

miles away,

and watch the Paris lights

come up at night.

Just to be on the safe side

you decide to stay completely

out of France.

But then the danger

seems too close

even to those boundaries,

and you feel

the timid part of you

covering the whole globe again.

You need the kind of friend

who learns your secret and says,

“See Paris First.”

![FullSizeRender[1]](https://ebeauvaisblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/fullsizerender11.jpg?w=1200)

![FullSizeRender[2]](https://ebeauvaisblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/fullsizerender2.jpg?w=1200)